Values as a guiding force supporting engagement and meaning-making

Poster presentation for the OTNZ-WNA conference 2023

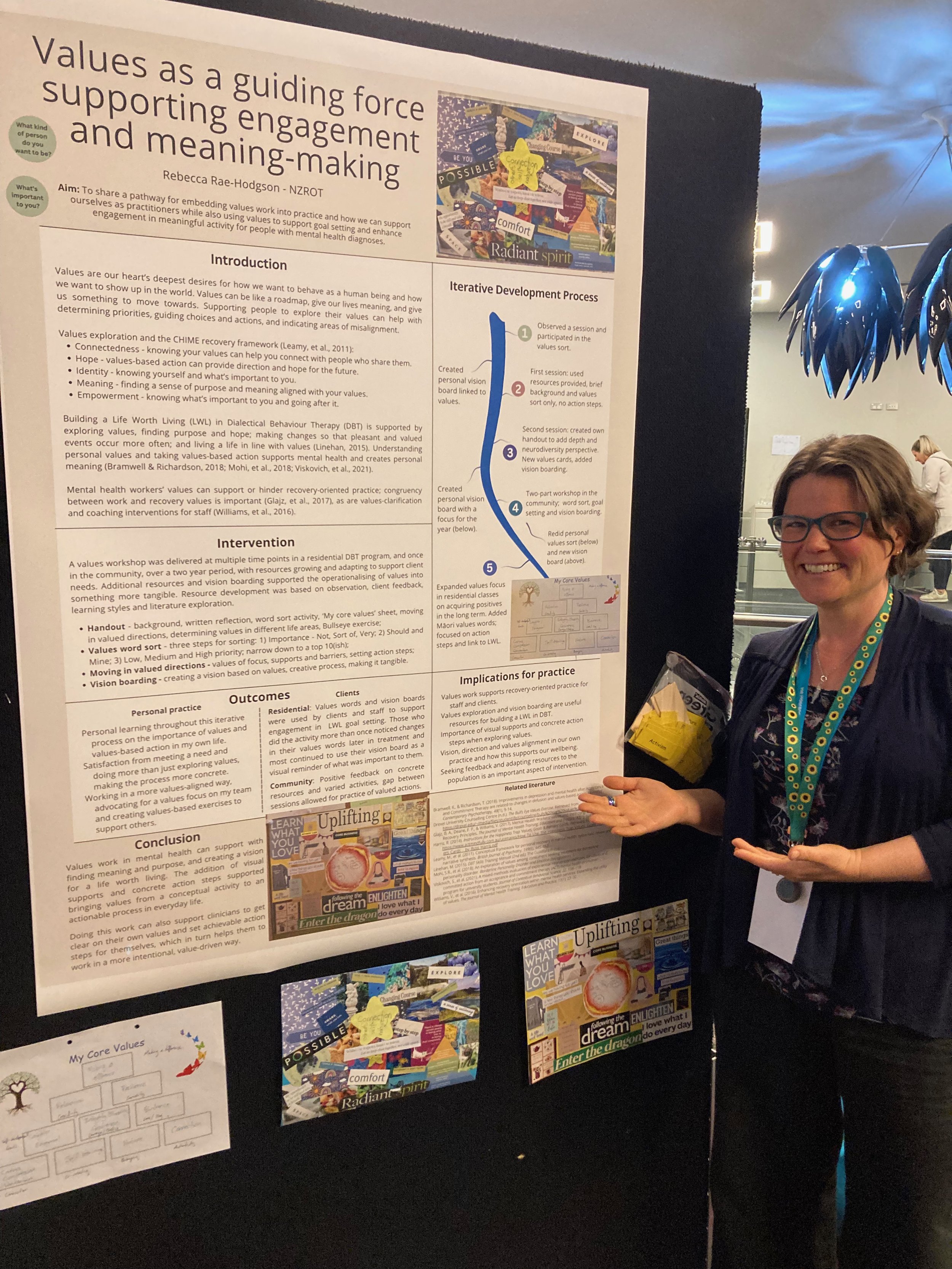

Image description: a photo of a brown haired person wearing blue glasses and a sunflower lanyard smiling at the camera and gesturing towards a conference poster. The poster is laid out in sections (text below) with a picture of a vision board at top right and bottom centre. A copy of these are hung below the poster.

Aim: To share a pathway for embedding values work into practice and how we can support ourselves as practitioners while also using values to support goal setting and enhance engagement in meaningful activity for people with mental health diagnoses.

Introduction

Values are our heart’s deepest desires for how we want to behave as a human being and how we want to show up in the world. Values can be like a roadmap, give our lives meaning, and give us something to move towards. Supporting people to explore their values can help with determining priorities, guiding choices and actions, and indicating areas of misalignment.

Values exploration and the CHIME recovery framework (Leamy, et al., 2011):

Connectedness - knowing your values can help you connect with people who share them.

Hope - values-based action can provide direction and hope for the future.

Identity - knowing yourself and what’s important to you.

Meaning - finding a sense of purpose and meaning aligned with your values.

Empowerment - knowing what’s important to you and going after it.

Building a Life Worth Living (LWL) in Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) is supported by exploring values, finding purpose and hope; making changes so that pleasant and valued events occur more often; and living a life in line with values (Linehan, 2015). Understanding personal values and taking values-based action supports mental health and creates personal meaning (Bramwell & Richardson, 2018; Mohi, et al., 2018; Viskovich, et al., 2021).

Mental health workers’ values can support or hinder recovery-oriented practice; congruency between work and recovery values is important (Glajz, et al., 2017), as are values-clarification and coaching interventions for staff (Williams, et al., 2016).

Iterative Development Process

Expanded values focus in residential classes on acquiring positives in the long term. Added Māori values words; focused on action steps and link to LWL.

Created personal vision board linked to values.

Observed a session and participated in the values sort.

First session: used resources provided, brief background and values sort only, no action steps.

Created personal vision board with a focus for the year (pictured at bottom of poster).

Second session: created own handout to add depth and neurodiversity perspective. New values cards, added vision boarding.

Redid personal values sort (pictured) and new vision board (top right).

Two-part workshop in the community; word sort, goal setting and vision boarding.

Intervention

A values workshop was delivered at multiple time points in a residential DBT program, and once in the community, over a two year period, with resources growing and adapting to support client needs. Additional resources and vision boarding supported the operationalising of values into something more tangible. Resource development was based on observation, client feedback, learning styles and literature exploration.

Handout - background, written reflection, word sort activity, ‘My core values’ sheet, moving in valued directions, determining values in different life areas, Bullseye exercise;

Values word sort - three steps for sorting: 1) Importance - Not, Sort of, Very; 2) Should and Mine; 3) Low, Medium and High priority; narrow down to a top 10(ish);

Moving in valued directions - values of focus, supports and barriers, setting action steps;

Vision boarding - creating a vision based on values, creative process, making it tangible.

Outcomes

Personal practice:

Personal learning throughout this iterative process on the importance of values and values-based action in my own life.

Satisfaction from meeting a need and doing more than just exploring values, making the process more concrete.

Working in a more values-aligned way, advocating for a values focus on my team and creating values-based exercises to support others.

Clients:

Residential: Values words and vision boards were used by clients and staff to support engagement in LWL goal setting. Those who did the activity more than once noticed changes in their values words later in treatment and most continued to use their vision board as a visual reminder of what was important to them.

Community: Positive feedback on concrete resources and varied activities, gap between sessions allowed for practice of valued actions.

Implications for practice

Values work supports recovery-oriented practice for staff and clients.

Values exploration and vision boarding are useful resources for building a LWL in DBT.

Importance of visual supports and concrete action steps when exploring values.

Vision, direction and values alignment in our own practice and how this supports our wellbeing.

Seeking feedback and adapting resources to the population is an important aspect of intervention.

Conclusion

Values work in mental health can support with finding meaning and purpose, and creating a vision for a life worth living. The addition of visual supports and concrete action steps supported bringing values from a conceptual activity to an actionable process in everyday life. Doing this work can also support clinicians to get clear on their own values and set achievable action steps for themselves, which in turn helps them to work in a more intentional, value-driven way.

Related literature

Bramwell, K., & Richardson, T. (2018). Improvements in depression and mental health after Acceptance and Commitment Therapy are related to changes in defusion and values-based action. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 48(1), 9-14.

Drexel University Counselling Centre (n.d.). The Bull’s Eye Values Exercise. Retrieved from: https://drexel.edu/~/media/files/studentlife/counseling/bulls%20eye%20values%20exercise.ashx?la=en

Glajz, B. A., Deane, F. P., & Williams, V. (2017). Mental Health Workers’ values and their congruency with Recovery Principles. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 12(1), 1–12.

Harris, R. (2014). Instructions for the Happiness Trap ‘Values, Goals & Barriers’ Cards. Retrieved from: https://www.actmindfully.com.au/upimages/How_To_Use_The_Happiness_Trap_Values,_Goals_And_Barriers_Cards_-_by_Russ_Harris.pdf

Leamy, M., et al. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445-452.

Linehan, M. (2015). DBT Skills Training Manual (2nd ed.). The Guildford Press.

Mohi, S.R., et al. (2018). An exploration of values among consumers seeking treatment for borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 5.

Viskovich, S., et al. (2021). A mixed-methods evaluation of experiential intervention exercises for values and committed action from an acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) mental health promotion program for university students. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 22, 108–118.

Williams, V., et al. (2016). Enhancing recovery orientation within mental health services: Expanding the utility of values. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 11(1), 23–32.